Matthew Brettingham 1699 - 1769

Matthew Brettingham the elder was an architect. He was born in Norwich, the son of Lancelot Brettingham (1664–1727) a mason and his wife, Elizabeth Hillwell (d. 1729). Both Matthew and his elder brother Robert were apprenticed, as bricklayers, to their father and, having served their time, both brothers were made freemen of the city of Norwich on 3 May 1719.

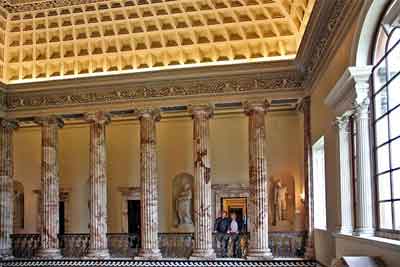

Matthew Brettingham's transition from builder and craftsman to architect was gradual. Pivotal to this process was his appointment in 1734, at an annual salary of £50, as clerk of works for the building of Holkham Hall on the north Norfolk coast, a large Palladian mansion based on the designs of William Kent with a major input of ideas from the patron, Thomas Coke, earl of Leicester. Brettingham's work at Holkham, which included the design of a number of structures in the park and was to extend over a score of years, earned him the respect and friendship of his employer and provided him with contacts which were to prove critical in the development of his career. His public work at this time, all within the bounds of Norfolk, included: the construction, in 1741, of Lenwade Bridge across the River Wensum; the rebuilding of the nave and crossing of St Margaret's Church in King's Lynn, damaged by the collapse of the spire in 1742; the raising of the new shire hall at Norwich Castle in 1747–9 and, over the same period, repairs to the castle itself; and repairs to Norwich Cathedral. Brettingham received a number of commissions for the design and remodelling of country houses in the 1740s which were initially confined to the county of Norfolk: the halls at Hanworth, Heydon, Honingham, and Langley were altered, while the hall at Gunton was an entirely new structure.

Matthew Brettingham's transition from builder and craftsman to architect was gradual. Pivotal to this process was his appointment in 1734, at an annual salary of £50, as clerk of works for the building of Holkham Hall on the north Norfolk coast, a large Palladian mansion based on the designs of William Kent with a major input of ideas from the patron, Thomas Coke, earl of Leicester. Brettingham's work at Holkham, which included the design of a number of structures in the park and was to extend over a score of years, earned him the respect and friendship of his employer and provided him with contacts which were to prove critical in the development of his career. His public work at this time, all within the bounds of Norfolk, included: the construction, in 1741, of Lenwade Bridge across the River Wensum; the rebuilding of the nave and crossing of St Margaret's Church in King's Lynn, damaged by the collapse of the spire in 1742; the raising of the new shire hall at Norwich Castle in 1747–9 and, over the same period, repairs to the castle itself; and repairs to Norwich Cathedral. Brettingham received a number of commissions for the design and remodelling of country houses in the 1740s which were initially confined to the county of Norfolk: the halls at Hanworth, Heydon, Honingham, and Langley were altered, while the hall at Gunton was an entirely new structure.

The outward extension of Brettingham's country-house practice in the late 1740s coincided, more or less, with his increasing presence in London which, for most of the next two decades, was the centre of his activity. His first major London commission was, appropriately, the building of Norfolk House in St James's Square for Edward Howard, ninth duke of Norfolk. Other work followed in St James's Square, Piccadilly, and Pall Mall. Engravings for the house in Pall Mall, raised in 1761–3 for Edward Augustus, duke of York, appeared in volume 4 of Vitruvius Britannicus, published in 1767. Brettingham's country-house work in these years included alterations to Goodwood, in Sussex (1750), Marble Hill, Twickenham (1750–51), Euston Hall, Suffolk (1750–56), Moor Park, Hertfordshire (1751–4), Petworth House, Sussex (1751–63), Wortley Hall, Yorkshire (1757–9), Wakefield Lodge, Northamptonshire (1759), Benacre House, Suffolk (1762–4), and Packington Hall, Warwickshire (1766–9).

Brettingham's architecture has been described as an unexciting, if dignified, variety of Palladianism. His practice was, however, successful, and the secret of his success was his ability to adapt the grander ideas of others to the purposes of his clients, confining himself to a limited number of design themes. His corner-towered scheme for Langley was, essentially, a restatement of the same theme at Holkham; the minimal Palladianism of Norfolk House, the façade of which was no more than blank walling relieved only by door- and window-cases and a parapet, a continuation of the minimalist treatment he had observed at Hanworth and which he himself had followed earlier at Gunton. Having encountered difficulties in obtaining ashlar, the earl of Leicester settled for the facing of Holkham Hall with white brick: Brettingham was to repeat the use of white brick at Gunton and again at Norfolk House, arranging, for Norfolk House, for the bricks to be made at Holkham and brought to London. Brettingham's forays into Gothic and his use of round arches, as in the nave arcades of St Margaret's, King's Lynn, and the galleried exterior of the shire hall in Norwich, indicate the approach of an engineer rather than an antiquary and are now seen as outlandish. It was towards the end of his working life, in 1761, that Brettingham published The Plans, Elevations and Sections of Holkham in Norfolk, with his own name inscribed on the plates as ‘architect’. Critics, from Horace Walpole onwards, have assumed that Brettingham was claiming the credit for Kent's designs but he himself may have used the inscription, legitimately from his view, to indicate his status as executive architect and draughtsman.

Matthew Brettingham died in his own house in the Norwich parish of St Augustine on 19 August 1769. He is buried in the local church alongside his wife, Martha Bunn (c.1697–1783), whom he had married on 17 May 1721.Nine children were born to him and his wife and all those for whom baptismal records have been identified were baptized in the church of St Augustine. Two of the sons Matthew Brettingham the younger (1725–1803) an architect and Robert Brettingham who was probably a worsted weaver are also recorded on the memorial stone.

Extract from article by Robin Lucas in the Oxford Dictionary of National Bibliography

The Monument

The monument comprises a plain stone which records Mathew's "Talent as an architect....Patronage and esteem of the nobility....and love of Palladian Architecture" - although it is unclear if the latter love relates to Matthew or his patrons.

Click here for a readable view of the inscription